The word stoma comes from the Greek for mouth or opening, and it refers to a section of the bowel brought to the surface of the body during surgery. This allows people with a stoma, known as ostomates, to pass an output of faeces (poo) and flatus (wind) into a bag attached to their abdomen—an appliance—instead of through the back passage (rectum).

The word stoma comes from the Greek for mouth or opening, and it refers to a section of the bowel brought to the surface of the body during surgery. This allows people with a stoma, known as ostomates, to pass an output of faeces (poo) and flatus (wind) into a bag attached to their abdomen—an appliance—instead of through the back passage (rectum).

A healthy stoma typically protrudes from the abdomen to form a moist spout, which is pink/red in colour. However, there are different types of stoma, the main kinds being a colostomy, an ileostomy or a urostomy. Understanding the difference between these, and which applies to you, is key to knowing how to care for your stoma.

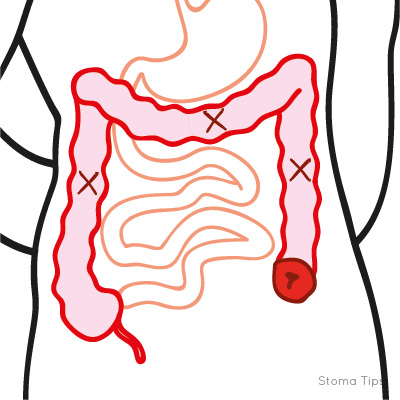

Colostomy

A colostomy is an opening into the large bowel (colon). It is typically red, and round or egg-shaped and sticks out only slightly from the skin surface (flush).

The output from a colostomy is typically formed and solid, although it may be looser immediately after surgery. This means colostomates should use a closed (non-drainable) appliance, which can be replaced from every few days to once or twice per day—commonly once per day.

A colostomy is often formed for people who have had rectal cancer, Crohn’s disease or diverticular disease, or, less commonly, for an imperforate anus or to treat faecal incontinence. As colostomies are usually intended to bypass the rectum, they are typically formed on the left-hand side of the body to, using the parts of the bowel closest to the rectum, known as the descending and sigmoid colon.

However, some people have a colostomy on the right-hand side of the abdomen, known as a transverse colostomy, ascending colostomy or cecostomy (depending on whether they are formed in transverse colon, ascending colon or cecum). These have a looser output and require a drainable pouch, which should be emptied four or five times a day.

Colostomy

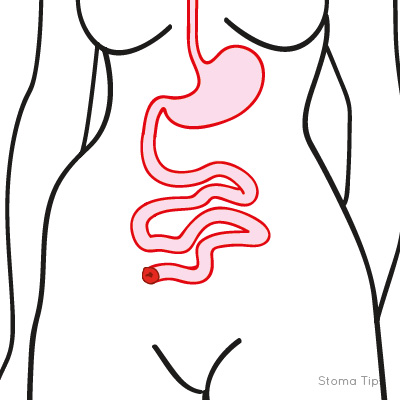

Ileostomy

An ileostomy is an opening into the small bowel (ileum) for passing faeces. In appearance, an ileostomy is red, round or egg-shaped and ideally formed with a small 2–3cm spout, to prevent leaking. This is usually on the right-hand side of the body, but can be on the left-hand side in some situations, depending on the patient’s body shape.

An ileostomy’s output is loose and semi-formed in consistency, sometimes likened to porridge. It therefore requires a drainable appliance, which can be emptied using an integral closure mechanism or clamp. An ileostomates will typically empty their appliance 4–6 times a day—including at night—and replace it completely every day or two. It can be worn for longer if necessary, particularly if a two-piece appliance is used.

Because drainable appliances do not need to be constantly taken on and off, they help prevent the skin from becoming irritated. Digestive enzymes in the liquid output make it corrosive to the skin, so care should be taken to ensure a good seal.

On average, an ileostomy will have a daily output of around 800ml, and is likely vary from around 600–1200ml (Burch, 2008). Should it produce over 1500ml a day, it is classified as a high-output ileostomy. The output’s consistency can be altered depending on what food and drink are consumed, and ileostomates should take particular care to stay hydrated.

Ileostomies are formed to bypass the entire large bowel, often in response to ulcerative colitis or bowel cancer. Those formed for bowel cancer are often temporary. Without the large bowel, it is harder for the body to absorb water and salt, which is what makes an ileostomy’s output looser.

Ileostomy

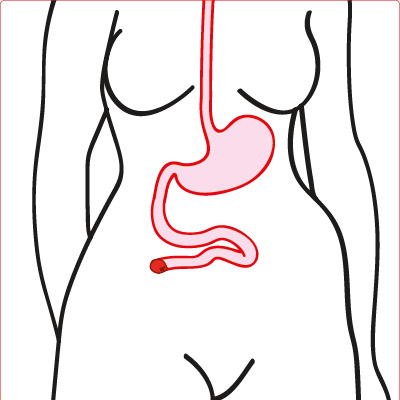

Jejunostomy

A jejunostomy is an opening in the early part of the small bowel (jejunum), closest to the stomach, for passing faeces and flatus. The output of a jejunostomy is especially loose and watery, and over a litre is usually produced a day. This requires a drainable appliance designed for high-output stomas. These typically have a high capacity, a large adhesive base and a connector at the bottom to attach to another, larger drainage bag. This will need frequent emptying, due to large quantities of faecal output collecting in the bag.

A jejunostomy is only created in extreme, rare cases, where most of the bowel, including the ileum, needs to be bypassed or removed. With any jejunostomy, it is especially important to carefully monitor and manage the fluid balance. Depending on how much bowel is left, it may not be possible to get enough nutrients through ordinary food. This is called short bowel syndrome and requires parenteral nutrition, where nutrients are delivered directly into the bloodstream.

Jejunostomy

Now and forever

Many stomas are permanent. These are often created for people who have lost normal use of their bowel, most commonly due to rectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease. If a person’s rectum or urinary tract needs to be removed, a permanent colostomy or urostomy makes it possible to continue passing faeces or urine through a different route.

Other stomas are created as a temporary measure. Temporary stomas are usually formed to divert faeces from a point further down the digestive tract. This may be where the bowel is healing from surgery, often after a cancerous section of bowel was removed and the ends rejoined, a procedure known as anastomosis, or it could be where the bowel has become obstructed. Once the bowel has either healed or been unblocked, stoma reversal surgery can be performed to reconnect the digestive tract.

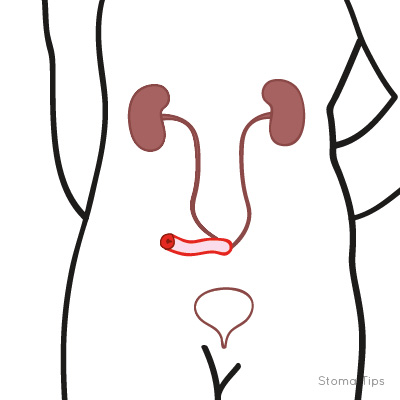

Urostomy

A urostomy is an opening into the urinary tract for passing urine. It typically has a small spout, which is red and round.

As a urostomy passes urine instead of faeces and flatus, its formation is more complicated than other stoma types. This involves detaching the ureters from the bladder attaching them to a repurposed piece of bowel, previously used for passing food, which is pulled through a hole in the abdomen. To make a typical urostomy, also known as an ileal conduit, a short section of the small bowel (ileum) is removed from the digestive system and attached to the ureters instead. Sometimes this is done with the colon, referred to as a colonic conduit. In rare cases, the ureters are brought out directly onto the abdomen.

A urostomy’s output is mostly made up of urine, with small amounts of mucus. This is held in a drainable appliance, fastened with a tap or bung. It should be emptied 4–6 times daily and replaced every day or two. To ensure an undisturbed sleep pattern, the appliance can be attached to a high-volume night bag. To avoid a urinary tract infection (UTI), urostomates should drink plenty of fluids; around 8–10 glasses of water daily are recommended.

Urostomies may be formed in response to bladder cancer or to treat interstitial cystitis. Depending on the condition, the detached bladder may be left in place or removed.

Urostomy

Loops, ends and barrels

Depending how a stoma is formed, it will be classified as either an end, loop or double-barrelled ostomy.

To form an end stoma, the bowel is cut and one end is pulled through the body wall. The rest of the bowel below the cut is either removed or closed shut inside the body.

In a loop stoma, a loop of intact bowel is pulled through the abdomen. This loop is then surgically divided into two ends: one functional end, which produces the output, and a non-functional end, which may produce some mucus. This make the two halves easier to reattach in reversal surgery.

A double-barrelled stoma is similar to a loop stoma, except that the two ends are disconnected and pulled through the skin surface at different points.

Conclusion

Knowing what type of stoma you have will help you know what precautions to take and what care products and routines may work for you. However, it is important to remember that every stoma is as unique as its owner is. It is always worth speaking to your stoma care nurse about how to personalise your prescription and your routine to ensure your stoma is as healthy, comfortable and hassle-free as it can be.

Elaine Swan is a colorectal nurse consultant at https://www.walsallhealthcare.nhs.uk/

Elaine Swan is a colorectal nurse consultant at https://www.walsallhealthcare.nhs.uk/

The contents of this page are property of MA Healthcare and should not be reused without permission